Hetty Green – The Witch of Wall Street

On a bustling Wall Street morning in the late 1800s, a solitary woman in a threadbare black dress made her way among the throngs of financiers. She carried an old handbag stuffed with papers, perhaps a few homemade oatcakes, and a grim determination on her face. This was Henrietta “Hetty” Green, dubbed by newspaper wags as the “Witch of Wall Street.”In an era of lavish excess known as the Gilded Age, Hetty Green defied every norm. She amassed a fortune rivaling the great tycoons of her time, all while eschewing the opulence and extravagance that defined her peers. Feared by some, mocked by many, and admired by a few, Hetty Green’s life story is a fascinating tale of financial genius, ironclad frugality, and a woman’s resilience in a man’s world.

Become a paid subscriber to get immediate access to The Ultimate Guide to Investing in Small Caps, or purchase it on Amazon.

In this Investment Compass Series installment, we journey through Hetty Green’s remarkable life – from her Quaker childhood and early business tutelage, through her rise as one of America’s richest investors, and into the legends of miserliness that earned her an infamous nickname. We’ll explore her investment strategies and philosophy, her personal eccentricities (cold oatmeal lunches and all), the historical Wall Street context she operated in, and the public controversies that swirled around her. Along the way, you’ll hear Hetty’s own words and those of contemporaries who knew or wrote about her, bringing to life the character behind the caricature.

Early Life: A Quaker Childhood Steeped in Finance

Hetty Green was born Henrietta Howland Robinson on November 21, 1834, in New Bedford, Massachusetts. She arrived into a wealthy Quaker family whose fortune was built on the thriving whaling industry. The Howland family owned one of New Bedford’s largest whaling fleets and also profited from global trade with China. From the outset, young Hetty was exposed to business and finance in a way few girls (or even boys) of her time were. When she was just two years old, her parents sent her to live with her grandfather, Gideon Howland, and her Aunt Sylvia, both of whom helped shape her financial acumen. As Hetty later recounted, her grandfather “would talk to her about financial matters and encourage her to read financial papers” while other children her age might have been playing with dolls. By age six, she was reading stock quotations, commodity prices, and shipping news aloud to her near-sighted grandfather as a sort of nightly ritual – “reading her stock market reports as other parents read bedtime stories,” as one writer described.

This early immersion paid off. By the time she turned 13, Hetty had effectively become the family bookkeeper, balancing ledgers for the Robinsons’ enterprises. She learned to read and interpret financial statements and even began trading commodities under her father’s guidance. Her father, Edward Mott Robinson, recognized Hetty’s aptitude. While her female classmates at Eliza Wing’s boarding school were groomed for society and marriage prospects, Hetty absorbed the lessons of commerce. She spent more time on the docks and in countinghouses with her father than in high society parlors. It was highly unusual for a woman in mid-19th century America to receive such a practical business education, but the Robinsons were anything but typical. They were Quakers – a faith known for its plain living and also for valuing women’s roles in family businesses – and they saw nothing wrong with a daughter mastering the family trade.

One telling anecdote from Hetty’s youth illustrates both her practicality and the values instilled by her father. On her 20th birthday, Edward Robinson reportedly bought Hetty a wardrobe full of fine dresses and gowns, hoping to help his only daughter attract a wealthy suitor in line with Victorian expectations. But Hetty had other ideas. She promptly sold offthose luxurious garments and “bought government bonds with the proceeds,” effectively turning frills into finance. It was a bold rejection of the era’s norms for women. As Hetty later said, “American women would be much happier if they learned the principles of business in girlhood,” rather than depending on marriages for security. She was intent on charting her own course, a theme that would define her life.

An Heiress with a Head for Numbers

Hetty’s early adulthood was marked by family fortunes and fierce willpower. By the 1860s, both her parents and her aging Aunt Sylvia were in declining health, and Hetty was poised to inherit substantial wealth. Her father’s trust in her abilities was strong – he had involved her deeply in managing the whaling and shipping business as his eyesight and the whaling industry’s prospects deteriorated. (The whaling boom peaked in the 1850s and waned after 1859, when petroleum was discovered, signaling a shift to kerosene and other fuels.) Edward Robinson sold off the whaling fleet ahead of the industry’s collapse and diversified into other shipping ventures, with Hetty by his side learning every step of the way.

When her beloved father died in 1865, Hetty inherited about $6 million – a massive sum for the time – but even that process did not unfold without drama. The real controversy came from her Aunt Sylvia’s estate. Sylvia Howland, Hetty’s maternal aunt, had been very fond of her but also very charitable. When Sylvia died in 1868, she left most of her $2 million estate to charity, not outright to Hetty. Hetty, who expected to be sole heir, was incensed. She contested her aunt’s will in court and even produced an earlier will that (conveniently) left everything to her, containing a clause explicitly voiding any later wills. The case, Robinson v. Mandell (1868), became notorious. Handwriting experts testified that the signature on the will Hetty presented was a forgery, and the court concluded the document was fraudulent. Hetty lost the case – one of the few defeats she ever accepted – and ended up settling for a smaller trust portion of Sylvia’s estate (around $600,000) instead of the full sum. The failed will gambit earned Hetty public notoriety early on. Newspapers painted her as greed personified: a woman willing to swindle charities for the sake of more gold.

Despite this scandal, Hetty’s primary inheritance from her father secured her financial independence. In an era when women typically could not control their wealth after marriage, Hetty took extreme measures to protect hers. In 1867, at age 33, she did marry – to Edward Henry (“Ned”) Green, a wealthy Vermont businessman several years her senior. But the marriage came with an unusual prenuptial agreement. Hetty insisted that her husband renounce any claim to her money, and legal arrangements were made so that her fortune remained solely in her name. This was highly unconventional (indeed, U.S. law was only just beginning to recognize married women’s property rights). Yet Hetty had good reason: as she wryly observed, she was “surrounded by gold diggers” and did not trust any suitor’s intentions. Edward Green turned out to be a genial man but a poor businessman. While he had a “modest wealth” of his own when they wed, his fortunes waned in the face of Hetty’s relentless frugality and control. Banks at first kept trying to treat Hetty’s accounts as under her husband’s authority – a common practice at the time – but she put a stop to that, fiercely defending her sole ownership. In fact, when banks in New York still presumed to use her funds as collateral for Edward’s dealings, Hetty separated their finances entirely and even lived apart from him for periods to ensure no one entangled her money with his debts.

Hetty and Edward had two children together – a son, Edward Howland Robinson Green (called Ned), born in 1868, and a daughter Harriet Sylvia Ann “Sylvia” Green in 1871. They spent the early years of marriage living in London (where the children were born), partly to stay away from the American spotlight after the will trial, and perhaps to indulge Edward’s social preferences away from Hetty’s watchful eye. But by 1875, the family returned to the United States, settling in Bellows Falls, Vermont – Edward Green’s hometown – as their home base.

Rise of a Financial Phenomenon

By her mid-30s, Hetty Green was not just a wealthy heiress – she was a full-fledged financier in her own right. She established an office in Manhattan and plunged into the thick of Wall Street investing, an almost unheard-of path for a woman of her day. Hetty had a simple, almost homespun investing philosophy that she articulated on many occasions: “I buy when things are low and nobody wants them. I keep them until they go up and people are crazy to get them. That is, I believe, the secret of all successful business.”. In other words, she was a contrarian investor decades before the term became popular, practicing what we now call “buy low, sell high”.

One of Hetty’s earliest big moves was in the aftermath of the Civil War. The U.S. government had issued “greenbacks” (paper currency not backed by gold) to finance the war, and after the war these notes traded at a deep discount due to doubts about the U.S. economy’s stability. While many investors dumped greenbacks for gold at barely 50 cents on the dollar, Hetty saw opportunity in the pessimism. She scooped up greenbacks on the cheap, confident that the U.S. government would eventually make good on its paper money. Indeed, her bet paid off handsomely: in 1875, Congress passed the Resumption Act, pledging to redeem greenbacks in gold, which caused their value to rebound to full face value. Hetty’s contrarian play turned a hefty profit and established her reputation for shrewd opportunism in troubled times.

Her investment portfolio grew to span railroad stocks, government bonds, real estate, and mortgages. She particularly liked investing in railroads and municipal bonds – tangible assets with reliable income – and she avoided the speculative cornering schemes that some infamous contemporaries indulged in. By reinvesting her earnings and rigorously compounding interest, she kept multiplying her fortune. Years later, financial writer Ken Fisher would note that Hetty’s strategy of targeting steady 6% returns and living frugally made her wealth far more durable than that of high-rollers like stock speculator Jesse Livermore, who made larger bets but often went bust.

Hetty’s ascetic personal life also directly supported her investing success. She believed in keeping costs minimal so that her capital could always be deployed for profit. As she put it, “[Thrift] enabled her to buy assets confidently amid financial panics because it prepared her to live on minimal expenses.”. In practice, this meant Hetty famously never spent a penny she didn’t have to. She wore the same somber black dresses for years until they were threadbare, mended them herself, and instructed her laundress to wash only the dirtiest parts (the hems) to save soap. She refused to keep a fancy office – instead, she conducted her business from a desk in the offices of Seaboard National Bank, where she could use space for free, often surrounded by suitcases filled with her documents and ledgers. Why pay rent for an office or home when that money could be earning interest? Hetty stayed in cheap boarding houses or rented modest flats under pseudonyms, moving frequently to avoid attention – and to dodge the New York City property tax on permanent residents.

All this penny-pinching fed her legend as the ultimate miser, but it also meant that when opportunity struck, Hetty Green always had cash on hand. She kept large reserves of liquid assets, ready to seize bargains during market crashes. “I believe in getting in at the bottom and out on top,” she said. “When I see a good thing going cheap because nobody wants it, I buy a lot of it and tuck it away.” True to that word, she often swooped in when others were panicking – buying real estate in foreclosure sales, snapping up stocks of railroads that had plunged in value, or lending money when credit was scarce. By the 1890s, her fortune was immense and still growing, even as her husband Edward’s finances deteriorated (he made some failed Wall Street bets and Hetty had to bail him out more than once). After one bailout too many – a disclosed $700,000 debt of Edward’s in 1885 that threatened one bank’s solvency – Hetty paid off his debts in exchange for seizing full control of all remaining family assets. It was said she never forgave Edward for his financial messes. Perhaps not coincidentally, from the mid-1880s on, she largely lived apart from her husband, setting herself and the children up in New York while Edward drifted between Texas (where he owned property) and other locales. When Edward Green died in 1902, Hetty did don mourning clothes – but in truth she had dressed in her austere black attire for years already, and she continued to do so, earning the “Witch” moniker in part from this perpetual widow’s wardrobe.

Hetty Green in a portrait from 1897, dressed in her typical austere black attire. Despite her immense wealth, she famously refused to indulge in fine clothing or personal luxuries.

The Witch of Wall Street: Frugality and Eccentricity

By the late 19th century, as Hetty Green’s wealth and notoriety grew, public fascination with her reached a frenzy. The press had a field day reporting on her peculiar habits. In the Gilded Age – a time when robber barons built palatial mansions and their wives draped themselves in jewels – Hetty’s refusal to spend money made her an anomaly. Journalists cast her as a miserly crone, playing up every anecdote of stinginess. Indeed, the Guinness Book of World Records later anointed her the “World’s Greatest Miser”. Among the (often exaggerated) tales: Hetty allegedly never turned on the heat in her apartments, never used hot water, and subsisted on meals of cold oatmeal and onions because she wouldn’t pay for fuel to cook. She wore undergarments until they fell apart and avoided medical bills at all costs.

The most shocking story concerned her son Ned’s health. It was widely reported that when young Ned injured his leg in a sledding accident, Hetty refused to pay a doctor and instead tried to have him treated at a free charity clinic, disguising him as a pauper. Recognized by staff (her grim face was too famous to fool the city doctors), she was turned away and decided to treat Ned’s injury at home with dubious home remedies like “oil of squills” and patent “liver pills”. Ned’s infection worsened terribly. Only after the boy’s father, Edward, intervened was Ned finally seen by a physician – but by then it was too late to save the limb. Ned’s leg had to be amputated, with his father reportedly footing the bill to avoid further haggling with Hetty. This gruesome tale of motherly stinginess appeared in newspapers far and wide, cementing Hetty’s reputation as a woman who “wouldn’t pay a doctor to save her own son’s leg.”

In fairness, some modern historians have questioned the full accuracy of this story. Evidence suggests Hetty did later spend considerable money and effort seeking specialist treatments for Ned, even relocating temporarily to be near a particular doctor. But the damage to her public image was done – the “Witch of Wall Street” seemed to care more about her gold than her flesh and blood. Hetty herself maintained that she never neglected her children’s well-being, but that she also wouldn’t spoil them with luxury. She raised Ned and Sylvia in spartan fashion: they wore hand-me-down clothes and lived plainly, often sleeping by her side on cots in cheap lodging houses. Love, in Hetty’s household, was never equated with lavish comfort.

As she aged, Hetty’s eccentricities only grew more colorful. She suffered from a painful hernia for over twenty years, yet stubbornly refused the surgical treatment. In 1915, when a doctor finally examined her, he found she had been holding in the hernia with a stick – literally binding a wooden stick against the protrusion under her undergarments, strapped in place with her leg and clothing. When the doctor told her she urgently needed an operation costing $150, Hetty erupted. Scooping up her fallen stick, she huffed, “You’re all alike! A bunch of robbers!” and stormed out rather than pay for the surgery. Such was her absolute refusal to part with money unless absolutely necessary.

Hetty’s paranoia about security also led to unusual behavior. She feared kidnappers and robbers (not an unfounded fear for one of the richest people in America), so she carried a .32 caliber revolver everywhere and even rigged it with strings to her bed when she slept in unfamiliar places. She wore a chain around her waist that held the keys to various safe deposit boxes where her negotiable securities were stored across multiple banks. She believed constantly moving between temporary residences – from Brooklyn to Hoboken and back – and taking different routes to her office would keep potential thieves or tax agents off her trail. In one episode, she abruptly moved her office from Chemical Bank to another bank after convincing herself someone at Chemical had tried to poison her coffee. True or not, it shows how distrustful she was of others’ intentions.

Through all of this, Hetty Green maintained a peculiar pride in her frugality. She often invoked her Quaker background as justification. In one interview, she explained calmly: “I am a Quaker, and I am trying to live up to the tenets of that faith. That is why I dress plainly and live quietly. No other kind of life would please me.”. She dismissed society’s criticism of her stinginess, saying, “I am not a hard woman. But because I do not have a secretary to announce every kind act I perform I am called close and mean and stingy.”. Indeed, there were rumors (mostly spread by her son later) that Hetty did give to charity discreetly and helped neighbors in need, albeit without fanfare. “I believe in discreet charity,”she told reporters, claiming she preferred to give anonymously and avoid encouraging beggars. Given the lack of public evidence, these claims were met with skepticism. As one observer quipped, her supposed beneficiaries were “not one was ever actually named and none came forward to identify themselves”. Whether or not she was secretly generous, Hetty clearly did not care to burnish her public image. She let the papers write what they would. “It has turned out…that my life is written for me down in Wall Street by people who…do not care to know one iota of the real Hetty Green,” she remarked, adding with a literary flourish, “I go my own way, take no partners, risk nobody else’s fortune, therefore I am Madame Ishmael, set against every man.”. In that stark statement, she likened herself to Ishmael, the outcast wanderer, suggesting she was misunderstood precisely because she was independent and earnest in her pursuits.

Not everyone saw her as a villain. Those in the financial community who dealt with Hetty often respected her competence. Some admiringly called her the “Queen of Wall Street,” noting that she often “lent freely and at reasonable interest rates” to banks, businesses, or even cities in distress. In fact, bankers who knew her acknowledged that despite her oddities, her word was good and her capital reliably available in a crunch. An associate once noted that she never cheated or scammed anyone – unlike many Gilded Age tycoons – and all her deals were above-board. Her ethical approach set her apart from contemporaries like Jay Gould or Daniel Drew, who were infamous for stock manipulation and fraud. Hetty took pride in the fact that she “risked nobody else’s fortune” in her ventures. This was true: she had no outside investors or partners; every deal she made was with her own money on the line. That independence, however, also made it easy for society to paint her as cold-hearted. A male mogul might be called “shrewd” for tough deals; a woman doing the same was labeled “heartless.”

Even fellow tycoons had mixed views of Hetty. Collis P. Huntington, the railroad baron who occasionally tangled with her on deals, sniped that Hetty was “nothing more than a glorified pawnbroker.” This jibe referenced how she profited from others’ misfortune – lending money or buying assets when desperate sellers had no other options – much like a pawnbroker who lends on collateral. It was partly envy, partly a begrudging acknowledgment that Hetty always drove a hard bargain. Indeed, she did foreclose on properties and call in loans ruthlessly when needed. If that made her a “witch” in some eyes, so be it.

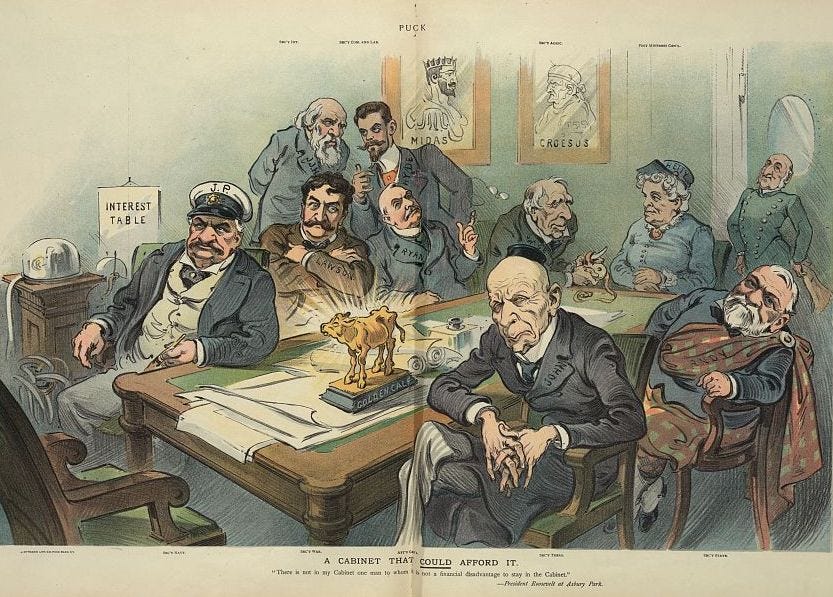

A 1905 satirical cartoon titled “A Cabinet That Could Afford It” pokes fun at the wealth and influence of the era’s tycoons. Here, artist J.S. Pughe imagines a U.S. President’s cabinet filled with millionaires: J.P. Morgan as Navy Secretary, John D. Rockefeller as Treasury Secretary, Andrew Carnegie as Secretary of State, and Hetty Green (the only woman in the scene) as “Postmistress General,” among others. A golden calf idol on the table symbolizes the worship of money. Such cartoons underscored how Hetty was ranked alongside the most powerful financiers of her day, even as the press mocked her as the “Witch of Wall Street.”

Panic of 1907: The Witch to the Rescue

By the turn of the 20th century, Hetty Green had weathered numerous financial panics and emerged ever richer. The Panic of 1907 was the ultimate test of her career – a nationwide credit crisis that threatened to bring down banks, businesses, and even the City of New York itself. While most moguls were caught off-guard by the market collapse in October 1907, Hetty had actually seen it coming. “I saw this situation developing three years ago… I said the rich were approaching the brink, and that a ‘panic’ was inevitable,” she explained afterward. True to her contrarian strategy, she had been quietly hoarding cash in anticipation of a downturn. When panic struck and banks could not provide liquidity, it was J.P. Morgan who famously convened the city’s bank presidents to stave off disaster. Incredibly, Hetty Green was the only woman invited to those emergency meetings with Morgan. She strode into the trust company boardroom amid the smoke and fury of frantic financiers – a small, plainly dressed widow among the pinstriped bankers – and offered her solution: her own money.

Hetty lent $1.1 million to the City of New York to help it meet obligations and pay salaries, taking her payment in short-term city bonds. She also extended loans to brokerages to keep them solvent. These were not acts of charity, of course – she earned solid interest and secured bonds as collateral – but her willingness to deploy cash when everyone else had none was vital. New York’s mayor acknowledged that the city “came to Green for loans to keep the city afloat” during that crisis. Her calm performance in 1907 bolstered her legacy as a “financial firefighter” of sorts. Those who had scorned her began to realize that Hetty’s conservatism – her piles of cash and refusal to speculate – actually served a stabilizing purpose. Those who knew her now referred to her admiringly as the “Queen of Wall Street,” noting that she lent “freely and at reasonable interest rates” when it mattered.

It’s worth placing Hetty’s rise in broader context. Wall Street in the late 19th century was essentially an old boys’ club of powerful men. Women were rarely seen on the trading floor, and certainly none were among the era’s famous financiers – except Hetty. This made her a curiosity and often a target of ridicule. The fact that she succeeded without the typical network of alliances (no Morgan bankrolled her, no political machine favored her) was remarkable. She was truly self-made in a time when married women had only recently gained the right to even hold property in their own name. In some ways, Hetty Green can be seen as a forerunner to later female investors and executives, proving that a woman could master high finance. She herself believed women should take charge of their money. “It is the duty of every woman, I believe, to learn to take care of her own business affairs,” Hetty opined. “A girl should be brought up so as to be able to make her own living… Whether rich or poor, a young woman should know how a bank account works, understand the composition of mortgages and bonds, and know the value of interest and how it accumulates.”. This quote, published in Ladies’ Home Journal in an era when women couldn’t even vote yet, was downright radical. Hetty practiced what she preached – teaching her daughter Sylvia bookkeeping and grooming her son Ned to manage real estate holdings – though with mixed success, as we’ll see.

Family and Later Years

In her later years, Hetty Green became something of a recluse, especially after the Panic of 1907. Her children were grown, and interestingly, they began to assert their independence from their formidable mother. Son Ned Green moved to Texas for a time to manage some of the family’s properties (including railroads and land in Texas that Hetty had acquired during foreclosure sales). Once free from Hetty’s direct supervision, Ned developed a taste for the high life that his mother had long denied him. After Hetty’s death, he would famously spend lavishly – building mansions, hosting extravagant parties, even constructing a yacht so huge that he got seasick and never used it. In open defiance of his mother’s values, Ned married a woman Hetty had openly disapproved of (a former corset salesgirl or, as rumor had it, a prostitute named Mabel) and surrounded himself with expensive hobbies like early radio technology. Yet, to his credit, Ned did maintain the core of the fortune – when he died in 1936, he still left a sizable estate to his sister Sylvia.

Daughter Sylvia Green, by contrast, stayed close to her mother well into adulthood – perhaps too close for Sylvia’s happiness. Hetty was notoriously suspicious of any man who courted Sylvia, believing every suitor was only after the Green fortune. Sylvia did not marry until age 38, when she finally convinced her mother that Matthew Astor Wilks (a minor heir of the wealthy Astor family, and thus possessed of his own $2 million) was not a gold-digger. Even so, Hetty forced Matthew Wilks to sign a strict prenuptial agreement waiving any right to Sylvia’s money. It seems Hetty wanted her legacy to remain intact under her bloodline’s control. After marriage, Sylvia lived more comfortably, though she and Matthew did not have children. And in a final act of quiet rebellion after a lifetime under Hetty’s frugal regime, Sylvia did something her mother likely never imagined: upon Sylvia’s own death in 1951, she left the entire remaining Green fortune to charity. It amounted to roughly $200 million (over $400 million in 1951 dollars, an even larger sum in today’s terms), and its donation was one of the grand philanthropic gestures of mid-20th-century New York. The woman whose mother could not abide “giving anything away” effectively gave it all away in the end. One might say that was Sylvia’s posthumous reply to Hetty’s creed of thrift.

As for Hetty Green herself, she lived out her final years in modest apartments in Brooklyn and Hoboken, still commuting by ferry or streetcar to her office at Chemical Bank on Broadway, still wearing that old black dress and bonnet. By 1905, one report noted she was “New York’s largest lender”, a testament to how much cash she controlled. Age and ill-health did not mellow her distrustful nature. Famously, an incident in her last year encapsulates her unyielding frugality: She got into a heated argument with a household maid over the price and virtues of skimmed milk versus whole milk – essentially scolding the maid for wasting money on rich milk. In the midst of that shouting match, Hetty suffered a stroke (or apoplexy, as they then called it). She never fully recovered. On July 3, 1916, at the age of 81, Hetty Green died in New York City, her children by her side.

At the time of her death, Hetty’s lifetime of parsimonious investing had made her arguably the richest woman in the world. Contemporary estimates of her net worth ranged from $100 million to $200 million. To put that in perspective, even the lower estimate of $100 million in 1916 would be roughly equivalent to $2.7 billion today; the higher figure would exceed $5 billion in 2024 dollars. Such wealth was virtually unheard-of for a self-made woman (or any woman) in that era. Little wonder the press, which had hounded her in life, paid grudging respect in death. The New York Times, two days after she died, ran an editorial titled “A Prodigy Because a Woman.” It captured the public’s conflicted view of Hetty Green’s life:

“It was that Mrs. Green was a woman that made her career the subject of endless curiosity, comment, and astonishment... Her habits were the legacy of New England ancestors who had the best of reasons for knowing ‘the value of money,’ for never wasting it, and for risking it only when their shrewd minds saw an approach to certainty of profit. Though something of hardness was ascribed to her, that she harmed any is not recorded... That there are few like her is not a cause of regret; that there are many less commendable, is one.”

In that single tribute, the Times acknowledged that Hetty Green’s gender made her a fascination, that her frugality had deep roots in Yankee tradition, and that while she wasn’t exactly beloved, she also wasn’t the villain many thought – in fact, plenty of others in the annals of Wall Street were far less ethical than she.

Legacy: Financial Genius or Miserly Cautionary Tale?

Hetty Green’s legacy has long been polarized. On one hand, she’s remembered in popular culture as the “Witch of Wall Street,” a cautionary tale of wealth without joy – a Scrooge-like figure who counted every penny but alienated society. Stories of her penny-pinching (some true, some embellished) have been told and retold for over a century. Even the Guinness Book enshrined her as history’s greatest miser, a moniker she likely would not have appreciated. On the other hand, modern financial historians and investors have sought to rehabilitate Hetty’s image as America’s first female financial tycoon, a woman who pioneered value investing well before it had a name. As Fortune magazine noted, if one strips away the colorful anecdotes, “these days, Green would likely be seen as an eccentric investing genius rather than just a miser”. Indeed, she practiced the core tenets that icons like Warren Buffett would later preach – living below your means, buying undervalued assets, focusing on long-term gains, and avoiding unnecessary risks. Hetty herself once summed up her philosophy in a sentence that could come straight from an investing handbook: “There is no great secret in fortune making. All you do is buy cheap and sell dear, act with thrift and shrewdness and be persistent.”. Simple advice, perhaps, but she proved how effective it could be.

Beyond the money, there is a feminist undercurrent to Hetty Green’s story that resonates today. She broke through barriers simply by refusing to conform. At a time when women couldn’t vote and were expected to stick to the domestic sphere, Hetty ran a one-woman financial empire that at various points held entire banks and cities at her mercy through enormous loans. She did so without leveraging a husband’s position or a father’s ongoing help – after her father’s death, it was all on her. In many ways, she had to be tougher and sharper than the male financiers around her to be taken seriously. And while they insulted her as unwomanly or “witch-like,” many also feared her acumen.

Her life, of course, is not a straightforward inspirational tale. There is a human cost to the kind of obsession Hetty had with wealth. One can admire her discipline and still wonder if her extreme thrift bordered on unhealthy fixation. She found contentment in austerity, quoting a favorite poem that began, “To live content with small means...”. But her children clearly suffered from a lack of normal comforts and warmth. Hetty may have won on Wall Street, but it’s arguable whether she found happiness – a question perhaps best answered by the legacy of her children, one of whom rebelled by spending lavishly, the other by giving everything away to charity. In that sense, Hetty Green’s story is also a meditation on what money means and what it should be for. She once said she valued money not for money’s sake but as a tool, yet she rarely allowed herself to use that tool to ease life’s little hardships.

In the end, Hetty Green remains a figure of enduring fascination. She was a creature of her time – embodying the Yankee thrift of old New England and the raw capitalist spirit of the Gilded Age – but also ahead of her time, a woman who showed that financial savvy knows no gender. She died over a century ago, yet lessons from her life are still discussed in personal finance articles and investing forums. Perhaps the best takeaway is a blend of both her shrewdness and a caution against her excesses. As the Morningstar analysts noted, we can learn a great deal from Hetty about patience, value investing, and self-reliance, even as we acknowledge that “discussions of her enormous self-made fortune are typically offset by tales of how cheap and mean she was.” Both sides of her legacy carry meaning.

Hetty Green often said she was content living plainly and independently, and by all accounts she remained lucid and calculating to the end. When she passed in 1916, newspapers couldn’t resist one last caricature – some claimed she literally died after arguing about skimmed milk to save a few cents. True or not, it’s fitting that the legend of the Witch of Wall Street would conclude on a note of thrift. But beyond the legend, Hetty Green’s real triumph was proving that financial acumen, resilience in crises, and unyielding determination can build an empire out of “cheap” stocks and bonds. She left an estate that made even the Astors and Vanderbilts take notice, yet she wanted no monument, no great mansion with her name. Her legacy instead lives on in financial history as a paradoxical icon: the richest woman of her time, draped in old black clothes; the Queen of Wall Street who lived in boarding houses; the shrewd dealmaker who could be both ruthless and principled. Hetty Green’s compass unwaveringly pointed to profit, but her story offers far more than just monetary advice – it’s a window into the complexities of wealth, gender, and reputation in America’s past.